Cleaner air’s impact requires a steeper reduction in human-emitted methane to meet global targets.

A new study reveals that reducing sulfur pollution in the air could unintentionally increase methane emissions from natural wetlands, including peatlands and swamps.

Published in Science Advances, the research suggests that declining global sulfur emissions—driven by clean air policies—combined with the warming and fertilizing effects of carbon dioxide, are fueling greater methane production in wetlands.

This additional release of 20–34 million tonnes of methane per year could make it more challenging to meet climate targets. As a result, efforts to reduce human-caused methane emissions may need to be even more ambitious than those outlined in the Global Methane Pledge.

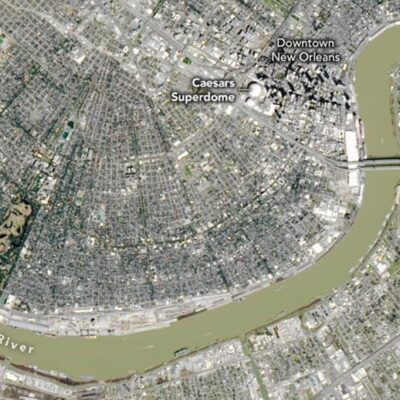

Methane, which is one of the most potent greenhouse gases in trapping heat in the atmosphere, is produced in wetlands around the world. Sulfur (in the form of sulfate) has a very specific effect in natural wetlands that reduces methane emissions, while CO2 increases methane production by increasing growth in plants that make the food for methane-producing microbes.

The Unintended Consequences of Clean Air Policies

Professor Vincent Gauci from the University of Birmingham and a senior author of the study said: “Well-meaning policies aimed at reducing atmospheric sulfur appear to be having the unintended consequence of lifting this sulfur ‘lid’ on wetland methane production. This coupled with increased CO2 means we have a double whammy effect that pushes emissions much higher.

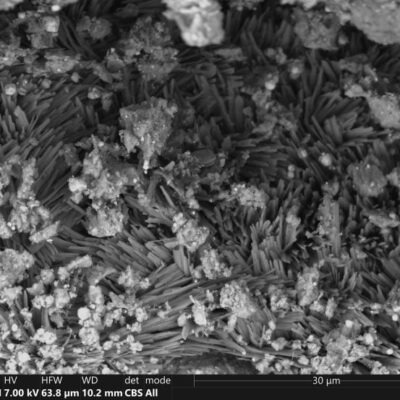

“How has this happened? Put simply, sulphur provides the conditions for one set of bacteria to outmuscle another set of microbes that produce methane when they compete over the limited food available in wetlands. Under the conditions of acid rain sulfur pollution during the past century, this was enough to reduce wetland methane emissions by up to 8%.

“Now that clean air policies have been introduced, the unfortunate consequence of reducing sulfur deposition, which does have important and welcome effects for the world’s ecosystems, is that we will need to work much harder than we thought to stay within the safe climate limits set out in the Paris agreement.”

The Global Methane Pledge and Unexpected Climate Feedbacks

More than 150 nations signed up to the Global Methane Pledge at COP26 in Glasgow, which seeks to reduce human-caused emissions of methane by 30% on a 2020 baseline, by 2030.

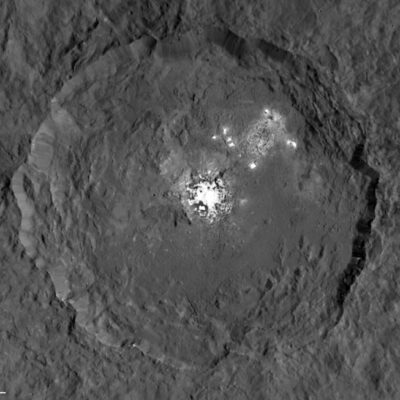

The study is the latest to implicate reductions in atmospheric sulfur in driving warming at a faster rate than anticipated. In 2020 shipping pollution controls were introduced to reduce emissions of sulphur dioxide and fine particles that are harmful to human health. This reduction in atmospheric sulfur over the oceans has been implicated in larger warming that expected in what has come to be known as ‘termination shock’.

Lead author of the paper Lu Shen of Peking University said: “Our study points to the complexity of the climate system. Representation of these complex biogeochemical interactions has not previously been well integrated into estimates of future methane emissions. We show that it is essential to consider these feedbacks to get a true understanding of the likely future of this important greenhouse gas.”