Harvard researchers have found that M. morganii may contribute to depression by producing an inflammatory molecule.

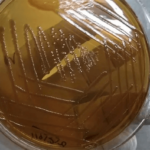

- Biochemical analyses reveal how the gut bacterium Morganella morganii may contribute to some cases of major depressive disorder.

- The bacterium incorporates an environmental contaminant into one of its molecules, triggering inflammation — a known factor in disease development.

- These findings suggest the contaminant could serve as a biomarker and further support the idea that major depressive disorder may have autoimmune connections.

Unraveling the Gut-Brain Connection

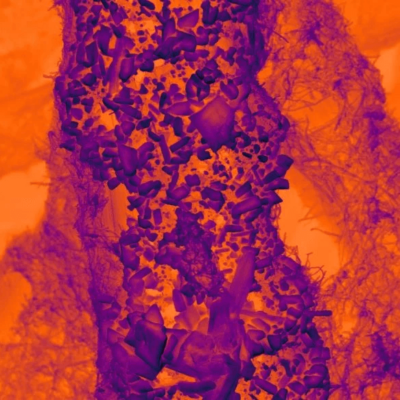

Researchers are uncovering more evidence that the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in overall health, including mental well-being. However, identifying which bacteria contribute to disease and understanding their exact mechanisms is still in its early stages.

One bacterium of interest is Morganella morganii, which has been linked to major depressive disorder in several studies. Until now, it was unclear whether this bacterium contributes to the disorder, whether depression alters the microbiome, or if another factor is involved.

A Breakthrough in Brain Health Research

A team from Harvard Medical School has now identified a biological mechanism that strengthens the case for M. morganii’s role in brain health. Their findings offer a plausible explanation for how this bacterium may influence mental health.

Published on January 16 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, the study points to an inflammation-triggering molecule that could serve as a potential biomarker for diagnosing or treating some cases of depression. More broadly, the research provides a roadmap for investigating how other gut microbes impact human health and behavior.

“There is a story out there linking the gut microbiome with depression, and this study takes it one step further, toward a real understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind the link,” said senior author Jon Clardy, the Christopher T. Walsh, PhD Professor of Biological Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS.

An Inflammatory Discovery

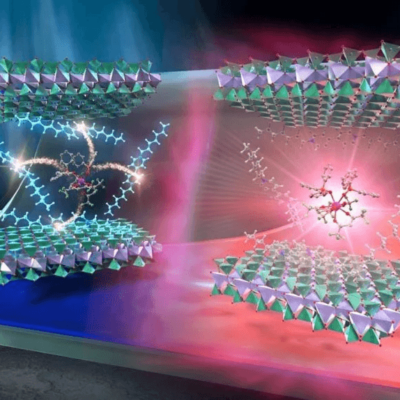

The study reveals that an environmental contaminant known as diethanolamine, or DEA, sometimes takes the place of a sugar alcohol in a molecule that M. morganii makes in the gut.

This abnormal molecule then activates an immune response that the normal molecule does not, stimulating the release of inflammatory proteins called cytokines, particularly interleukin-6 (IL-6), the team found.

This tells a coherent story from M. morganii at the beginning to depression at the end, the authors propose, since chronic inflammation contributes to the development of many diseases and has been linked with depression.

The connection is further strengthened by previous studies associating IL-6 with major depressive disorder and linking M. morganii with inflammatory conditions such as type 2 diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Future research will be needed to confirm this faulty product of M. morganii as a definitive cause of major depressive disorder and to gauge what percentage of cases it may be responsible for.

A New Handhold for Tackling Depression

DEA is used in industrial, agricultural, and consumer products.

“We knew that micropollutants can be incorporated into fatty molecules in the body, but we didn’t know how this occurs or what happens next,” Clardy said. “DEA’s metabolism into an immune signal was completely unexpected.”

The team proposes that DEA could be added to the growing list of biomarkers used to detect some cases of major depressive disorder.

Reframing Depression as an Immune Disorder

The study also strengthens arguments that major depressive disorder, or a subset of cases, could be considered an autoinflammatory or autoimmune disease and be successfully treated with immune modulator drugs, Clardy said.

More broadly, revealing how a bacterial product can alter human immune function by incorporating a contaminant opens the door to probing the effects of other gut bacteria in immunity and other human biological systems, the authors said.

“Now that we know what we’re looking for, I think we can start surveying other bacteria to see whether they do similar chemistry and begin to find other examples of how metabolites can affect us,” said Clardy.

Connecting Labs to Connect the Dots

The advance was enabled by combining the Clardy Lab’s focus on the chemistry of small, medically relevant, bacteria-made molecules with the lab of Ramnik Xavier, the HMS Kurt J. Isselbacher Professor of Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, which has expertise in uncovering how the microbiome affects health and disease at the molecular level.

Decoding the Microbiome’s Impact on Disease

The team’s collaborations in recent years have pushed boundaries in deciphering the mechanisms that drive the interplay between gut bacteria, the immune system, and health outcomes. These include:

- Achieving the rare feat of connecting a single bacterium (A. muciniphila), the molecule it makes, the pathway it operates through, and the biological outcome (protecting against inflammation and raising sensitivity to cancer immunotherapies).

- Showing that the gut bacterium R. gnavus produces an immune-stimulating sugar-molecule chain that could explain its association with Crohn’s disease and IBD.

- Discovering that a seemingly innocuous fatty molecule on the surface of the “strep throat” bacterium S. pyogenes can actually activate the immune system to release inflammatory cytokines — explaining why the bacterium sometimes leads to serious immune complications, how it may contribute to autoimmune diseases like lupus, and how cancer immune therapies might be improved.

That fatty molecule belongs to a family known as cardiolipins, and the team has gone on to show that other cardiolipins can trigger cytokine release. In the new study, the researchers were surprised to discover that when DEA gets substituted into the molecule M. morganii makes, the molecule begins to act like a cardiolipin.