A study on bat genomes, involving Texas Tech University, discovered genetic adaptations that help bats resist viral infections, including COVID-19. Researchers found that a bat gene, ISG15, can reduce SARS-CoV-2 production by up to 90%, while the human version showed no effect.

Five years after the COVID-19 outbreak, scientists worldwide continue to study its long-term effects and explore strategies to mitigate future pandemics. Now, an international team of researchers may have uncovered a crucial piece of the puzzle—with a laboratory at Texas Tech University playing a key role.

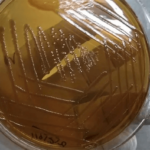

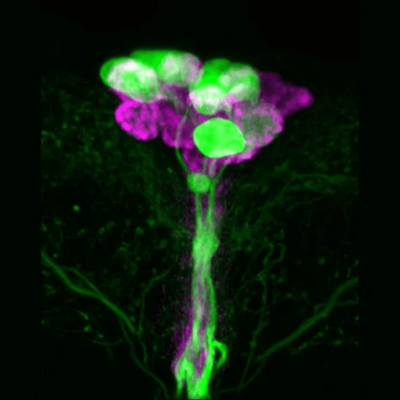

The Ray Laboratory, led by Professor and Associate Chair David Ray of the Department of Biological Sciences, contributed to a study on bat genomes published in Nature. Their research identified specific genetic components in a bat species that exhibit greater immune system adaptations compared to other animals.

The study found that a particular gene in some bats can reduce SARS-CoV-2 production by up to 90%, a discovery that could pave the way for new medical approaches to combating viral diseases.

“Bats have an amazing ability to resist some of the worst effects of viral infection that make us so vulnerable to certain diseases,” Ray said. “While we get very sick, the bats barely blink an eye when exposed to the same pathogens.”

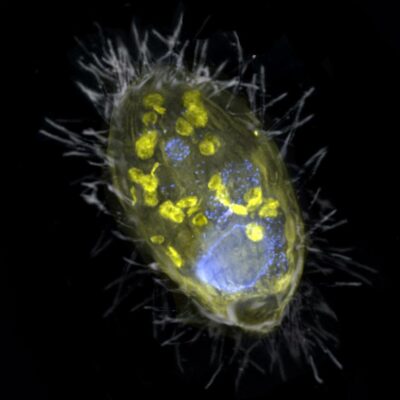

Ray said his laboratory aided in the annotation of the genome assemblies in the bats. Genome annotation is how scientists characterize all component parts of the genome – the genes, regulatory sequences and non-coding and coding regions. The Texas Tech lab identified the transposable element (TE) regions of the assemblies, where bits of DNA can create new copies of themselves and introduce variations within the genome.